Ms. McDonnell described preliminary results from an ongoing project on schizophrenia and weight gain. Her group's research suggests that weight gain in persons with schizophrenia not only has detrimental effects on general health, but also decreases quality of life and medication compliance.

Previously, this research group had conducted an analysis of the relationship between body mass index and medication non-compliance. They found that the proportion of patients with schizophrenia who missed medications increased with elevated body mass index. Similarly, the frequency of stopping and switching medications also increased with increases in body weight and body mass index.

In the current study, McDonnell and colleagues examined effects of stopping and switching medication on health care outcomes. Specifically, they assessed the impact of recent weight gain on the acute use of hospital and emergency services by schizophrenic patients. These results were presented at the World Congress of Biologic Psychiatry.

Data came from an eight-page, self-report questionnaire covering general health care attitudes, including schizophrenia history and treatment patterns. Approximately 400 patients participated in the survey, which included questions about weight gain and use of acute medical services.

Patients reported whether they had gained or lost weight in the preceding six months, and, if so, how much. They also reported whether they had visited a hospital or emergency room in the preceding six months.

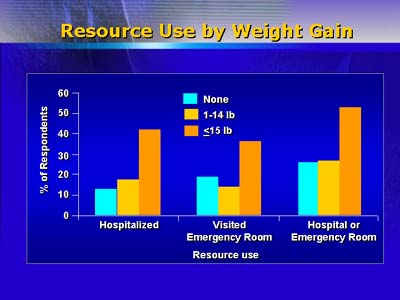

The mean weight change for the total group was an increase of about 4.5 pounds (2.0 kg), with 22% of patients reporting weight gain of at least 15 pounds (6.8 kg). About 24% of the patients reported a hospital visit and 26% reported an emergency room visit. Thirty-eight percent of patients reported both hospital and emergency room visits.

The degree of weight gain was positively correlated with the use of acute care medical services. Patients who reported gaining at least 15 pounds (6.8 kg) had a statistically significant increase in hospitalizations and emergency room visits than did patients who reported no weight gain.

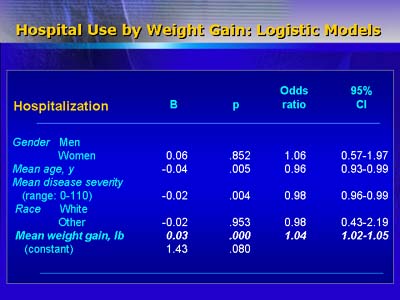

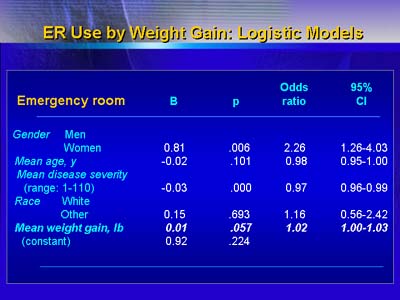

McDonnell and colleagues used logistic regression analysis to control for factors other than weight gain (such as age, sex, race, and severity of illness) that may have affected the use of acute care facilities. They found a statistically significant, persistent relationship between weight gain and increased use of health care services.

The authors found the likelihood of hospitalization increased by 1.04 times for every one pound of weight gained. The odds ratio for emergency room use was 1.02, and the odds ratio for combined hospitalization and emergency room use was also 1.02.

The authors concede several possibilities that may account for the correlations they observed. Patients who are doing poorly may be more likely to come to hospitals or emergency rooms, where physicians may switch them to other medications, such as atypical anti-psychotics associated with weight gain. Patients may be more likely to need acute services after a rapid weight gain that is unrelated to their medication. Another possibility is that patients who gain weight may be more likely to discontinue medication, suffer relapse or symptom exacerbation, and require hospital or emergency room services.

To illuminate those possibilities, the authors intend to follow patients prospectively while studying medication compliance, medication type, and use of acute medical services.