Dr.

Byrne reported findings of a survey of behavioral and psychological

symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in clinical practice in Europe.

Apathy was the most common symptom. The survey questionnaire

examined BPSD in the context of caring, and included symptoms

that are not addressed in other BPSD measures.

The symptoms of BPSD are

a common cause of distress to patients and their caregivers.

However, what constitutes BPSD differs according to various

classification systems and guidelines. The standard measure

of BPSD is the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). However,

this measure does not address the qualitative aspects of BPSD,

such as the time of occurrence or the consequences of the

unwanted behavior. Thus, there is a danger that clinicians

will see only the behavior, ignoring the dynamic aspects of

that behavior in the patient.

To address these concerns, the European Alzheimer’s

Disease Consortium (EADC) conducted a survey of BPSD in clinical

practice. The survey population included patients and caregivers

from 12 centers in Europe.

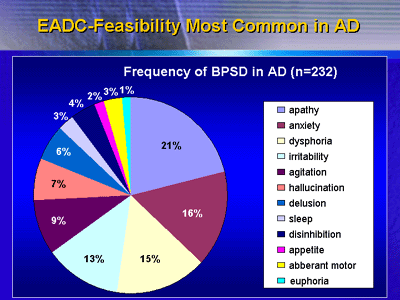

Of 698 patients entered, 368 (52.7%) had Alzheimer’s

disease. Of that group, 232 (63%) had BPSD. By comparison,

Lyketsos et al. published a U.S. investigation in 2002 called

the Cardiovascular Health Study. For all dementia patients

in this study, 62% had clinically significant neuropsychiatric

symptoms as defined by the NPI.

According to the results of the EADC survey,

the most common BPSD symptoms in the 232 Alzheimer’s disease

patients with BPSD included apathy (21%), anxiety (16%), and

dysphoria (15%). Sleep was relatively uncommon (3%). In contrast,

Lyketsos and colleagues found sleep symptoms to be more common

(13%). However, the magnitude of the apathy measure was similar

(18%). Dr. Byrne said investigators expected some difference

in prevalence, since the populations were not identical. Thus,

the relative frequency of any BPSD symptom appears to depend

very much on the population under study.

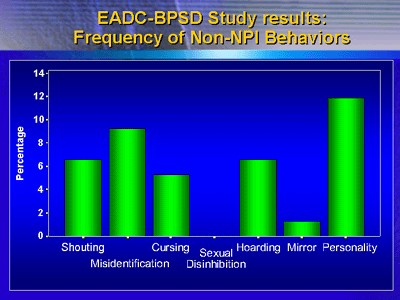

The survey results included some behaviors

and symptoms that are not included in the NPI. Changes in

personality were quite frequent, as were misidentification,

shouting and hoarding.

The EADC survey also looked at duration of

symptoms. They found that 50% of the subjects did not present

to clinicians until 2 to 5 years after symptom onset. Dr.

Byrne said this is worrying, since investigators consider

early diagnosis to be important. For the subset of patients

with Alzheimer’s disease, a somewhat smaller percentage of

patients (45%) presented 2 to 5 years after symptom onset.

The EADC researchers asked not only about

frequency and duration of BPSD, but also about the qualitative

aspects of BPSD.

About 34% of responders said that BPSD symptoms

were a problem in the daytime, while 20% said the symptoms

were not time-specific. About one-third said the behaviors

are a problem in the home, while 47% said the behaviors were

not specific to any place. The behaviors were a problem to

30% patients and 44% of caregivers.

Investigators asked what starts the behavior,

but in most cases (70.9%) responders could not identify a

trigger. However, a few cited tiredness (6.3%) and being left

alone (3.8%).

The consequences of BPSD included impairment in activities

of daily living (16.5%) and depression, anxiety or tiredness

(13.9%).

Dr. Byrne said the effect on the mood of the

patient is a notable finding. Previously, there was data showing

that BPSD affect the mood of the caregiver. Now, the EADC

provides preliminary data that these behaviors can also affect

the mood of the patient.

For the future, EADC researchers hope to elucidate

cross-cultural differences in BPSD in North, South and Mediterranean

Europe. They are also interested in conducting intervention

studies, particularly with regard to apathy.

|