| A

wide range of epidemiologic and other studies indicate that

four risk factors for cardiovascular disease---hypertension,

abnormalities in glucose and insulin levels, cigarette smoking,

and obesity--- are also risk factors for vascular cognitive

impairment and dementia. Hypertension (particularly high systolic

blood pressure) appears to be the strongest predictor of significant

cognitive impairment in the elderly. Dr. Gorelick reviewed the

literature and explained a possible mechanism for cerebral neurotoxicity

through primary disruption of endothelium in the brain’s blood

vessels. As a conclusion, he stressed the importance of diagnosing

and treating hypertension. Aggressive midlife medical care for

cardiovascular disease may have significant benefits in decreasing

the risk for late-life vascular cognitive impairment and dementia.

Dr. Gorelick opened by noting that studies

have suggested certain genetic and clinical characteristics

are associated with healthy aging. For instance, there may

be roughly 1000 genes associated with longevity, with at least

one major gene localized to chromosome 4. There are multiple

clinical characteristics shared by those who live long and

in good health. Four such traits are low blood pressure, low

serum glucose, no cigarette smoking, and no obesity.

When viewed differently, it is clear that risk factors for

cardiovascular disease --- hypertension, abnormal glucose

and insulin levels, cigarette smoking, and obesity --- are

also risk factors for cognitive health in late life. Based

on data from numerous studies, hypertension, especially elevated

systolic blood pressure, appears to be the strongest predictor

of vascular cognitive impairment and dementia among the elderly.

Older research uses the model of vascular dementia to understand

pathologic cognitive declines. Imaging and etiologic studies

of patients with vascular dementia identify subtypes such

as multi-infarct dementia, as well as dementia associated

with a strategically important infarct (often involving the

angular gyrus or thalamus) or dementia associated with diffuse

subcortical damage.

Over time, the model has shifted to one of vascular cognitive

impairment characterized by a combination of etiologic and

clinical traits. Vascular cognitive impairment is actually

a spectrum of syndromes that have decreased cognitive ability

across multiple domains at their centers. Impairment can range

from slight to severe, and the time course ranges from sudden

to subacute to slow development and progression.

Multiple direct causes have been identified, including clinical

and silent strokes. Pathologic findings include microvascular

disease, large-artery disease, deposition of A-beta peptide,

or cerebral hemorrhage. Vascular cognitive impairment embraces

a variety of heterogeneous syndromes, and distinction from

Alzheimer’s dementia and direct stroke effect, both common

in the elderly, complicates the research and clinical picture.

Gorelick restated the research and clinical problem from

the public health perspective: ‘Can you identify early-phase

vascular cognitive impairment and intervene to prevent dementia?’

He believes the answer is ‘Yes.’ He noted epidemiologic studies

suggesting that roughly half of people with cognitive impairment

but no dementia develop dementia in five years, which suggests

there may be a target for preventive intervention. A twin

study showed that the twin with higher midlife systolic blood

pressure, metabolic abnormalities involving glucose and/or

insulin levels, or both was at higher risk for late-life dementia.

|

Population Attributable

Risk (PAR)

of Select Modifiable Stroke Risk Factors

for Vascular Cognitive Impairment

Factor

|

Relative

Risk |

Prevalence |

PAR |

| Hypertension |

8.7 |

25% |

66% |

| Diabetes mellitus |

1.8 |

10% |

8% |

| LDL-cholesterol |

2.6 |

36% |

37% |

| Atrial fibrillation |

1.5 |

4% |

2% |

| Current cigarette smoker |

1.8 |

25% |

17% |

Alcohol:

2-5 drinks/day |

1.8 |

7% |

5% |

Source: Gorelick P, 2003

|

He moved from an understanding of vascular cognitive impairment

and dementia and their risk factors to study of possible mechanisms

through which risk factors might contribute to clinically

evident cognitive decline.

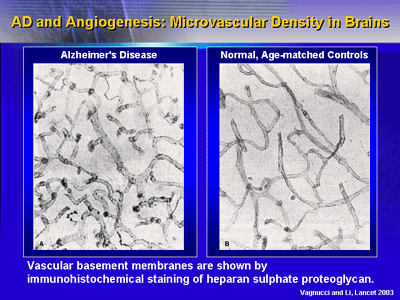

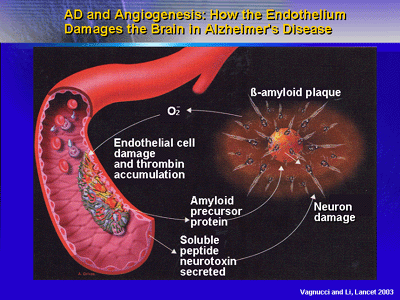

He presented findings from a 2003 paper on Alzheimer’s disease

and microvascular angiogenesis to frame the hypothesis that

cerebrovascular damage (specifically, disruption of the endothelium

and its action as a blood-brain barrier) can lead to neurotoxic

effects through a combination of soluble factors and deposition

of beta-amyloid protein.

Neurotoxicity may be evident clinically as Alzheimer’s disease

or as vascular cognitive impairment or nonAlzheimer’s dementia.

Gorelick placed studies that did not find a link between

risk factors, especially hypertension, and cerebrovascular

disease and dementia in context by emphasizing that blood

pressure is known to decrease as cognitive impairment worsens.

He believes some studies may have missed a link between hypertension

and vascular cognitive impairment by evaluating people too

late in the course of their clinical presentation.

Gorelick concluded that research work as varied as epidemiologic

studies on healthy aging to anatomic and molecular work on

dementia lead to the same conclusion: Control of vascular

risk factors by midlife can decrease the risk for vascular

cognitive impairment and dementia at the end of the lifespan.

Hypertension is probably the most important target for such

intervention.

|