|

Dr. Fischbach, a distinguished neuroscientist

who has served at universities and the National Institutes of

Health, addressed the progression of neuroscientific understanding

from the basic research findings of the 20th Century

to the current possibilities inherent in the integration of

neuroscience with clinical medical work. He used neurodegenerative

disorders, including Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia,

to illustrate many points.

Dr. Fischbach opened by noting that he would be addressing

three major groups in 2002−the American Psychiatric Association,

the American Neurological Association, and the American Neurosurgical

Association−and that this breadth of audience reflects the

growing understanding within different medical specialties

that much of the basic science underlying different clinical

developments is the same.

He noted that Sigmund Freud moved from electrophysiologic

work to psychological conceptualization because he needed

to seat his results within a theory of mental life. In contrast,

current scientists will use improved understanding of psychopathology

and psychopharmacology to revolutionize theories of cognitive

understanding and mental life.

Dr. Fischbach laid the groundwork for the remainder of his

talk in a discussion of the diversity of known neurodegenerations

(see Table), all of which at some level raise the question

of how to activate and deactivate apoptotic neuronal loss.

|

A sampling of neurodegenerations

at different stages of life.

| Disorders of the aging brain: Alzheimer's

disease, Parkinson's disease | | Disorders of younger adults: Huntington's

disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, prion diseases | | Disorders

of children: spinocerebellar ataxia, Tay-Sachs

disease and other storage diseases |

|

|

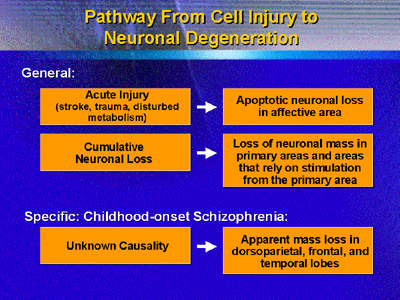

He laid out a general framework that may apply to many of

these seemingly diverse conditions:

Dr. Fischbach noted that the mass loss with schizophrenia

can be quite large, in the magnitude of 2-3% loss per year,

especially in the dorsoparietal cortex. With this knowledge,

he believes researchers can find clues to the region of the

brain within which the disordered thought of schizophrenia

begins (the dorsoparietal cortex). When region can be confirmed,

studies to arrest or reverse neuronal loss in the target region

may begin.

This transition from understanding of key areas to work

in arresting or reversing neurodegeneration has already occurred

with Parkinson's disease, where he noted the success of pilot

studies that targeted regions within the subthalamic nucleus

for deep-brain stimulation.

In one case, functional magnetic resonance during electrode

placement allowed researchers to place an electrode so precisely

that the patient's contralateral motor symptoms were extinguished.

Initial results from some studies suggest that long-term stimulation

may even have trophic effects.

In summary, he believes it likely that much of the current

functional and imaging work done with psychiatric conditions

will reveal key locations of neuronal dysfunction and loss.

Once target locations are established, further work may reveal

the mechanisms through which loss occurs and the means through

which loss can be arrested or reversed.

He closed with an observation drawn from work with Parkinson's

disease: When the earliest clinical signs are seen, roughly

75% of neurons in the target region have already been lost.

Thus, early diagnosis of individuals at risk for disease or

presenting with early-stage disease is critical to improved

care and better prognosis.

|