|

Depression is strongly associated with

a worse prognosis in patients with established coronary artery

disease. Despite the evidence, there have only been two trials

of depression treatment in this patient population. Physicians

need to consider depression as a risk factor in patients with

established coronary artery disease and treat it when appropriate.

More treatment trials should be conducted.

Depression is a potential new risk factor for coronary artery

disease (CAD), similar to obesity and lack of exercise. There

is emerging evidence to suggest that although depression may

not cause CAD, treating depression would be prudent in such

patients.

The prevalence of major depression is high in hospitalized

CAD patients. There is good data to suggest that major depression

is at least 3 times as common in these patients as in the

general community for hospitalized patients. This is true

in a variety of populations, including myocardial infarction,

unstable angina, congestive heart failure and post-intervention

patients.

Interestingly, minor depression is also about 3 times as

common in hospitalized CAD patients. This means that about

one third of these patients show some degree of depression

during hospitalization.

It is difficult to predict which CAD patients will exhibit

depression. However, it is more common in women, younger patients,

individuals with poor social support and patients with more

severe CAD.

Researchers do not know exactly what causes depression.

It is likely that a combination of genetics, unhealthy lifestyles

and previous stresses create physiologic susceptibility. Then,

stressful life events or chronic stress can interact with

this susceptibility. This causes neuroendocrine disturbances

that result in depression.

It is possible that there is a link between the causes of

depression and CAD. There is no causal link. However, the

neuroendocrine disturbances of depression may have an impact

on the platelet changes, inflammation and autonomic nervous

system disturbances that contribute to atherosclerosis.

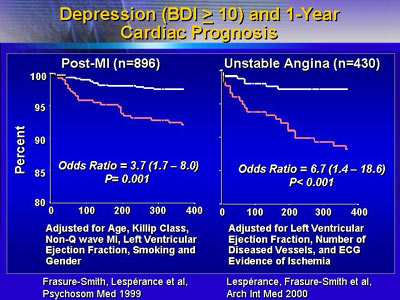

Dr. Frasure-Smith and colleagues have studied the psychosocial

aspects of acute coronary syndromes. They have looked at 896

post-myocardial infarction patients and 430 patients with

unstable angina who all received usual care (31% women).

The investigators found that depression had a marked impact

on 1-year prognosis, even after adjusting for other major

cardiac risks. The impact was most pronounced in the first

6 months, then decreased somewhat.

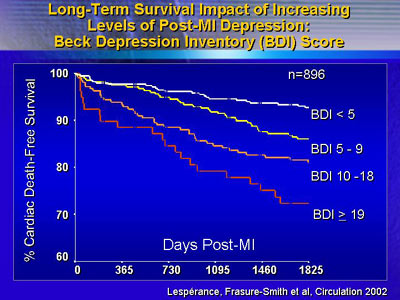

They also found a dose-response relationship. Patients with

worse depression had a worse prognosis. This suggests there

may be no safe level of depressive symptoms for CAD.

This is not the only study to suggest a dose-response relationship

between depression and CAD outcomes. A 1996 study in the American

Journal of Cardiology looked at depression severity in 1,250

catheterization patients. More deaths occurred in patients

with moderate/severe depression compared with patients who

had mild depression. Adjusting for other cardiac risks, the

investigators found that long-term risk of mortality was significantly

higher in patients who were depressed.

Consistent results emerged from a more recent study of older

patients. A 2001 study in the Archives of General Psychiatry

looked at patients age 55 to 85 years with a history of angina,

myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure.

There are no prospective studies yet to demonstrate whether

treating depression can alter CAD prognosis. However, Dr.

Frasure-Smith believes that there is enough evidence to justify

additional trials. That evidence should compel physicians

to consider depression as a risk factor in patients with established

CAD.

|